We use Word documents all the time. But do you ever stop to think about accessibility? Even basic documents can include elements that make them inaccessible to some users. Like tables, or images.

If your Word document is more complex, it can mean more accessibility challenges.

Why Word document accessibility matters

Accessibility isn’t just for websites. Everything you do at work should be inclusive. So it’s good practice to make sure your Word documents are accessible. Whether it’s internal within your organisation or external. Can you guarantee it won’t be shared with someone who’s disabled?

Here are some tips to help make your Word documents more usable and accessible.

Use accurate link text

Links direct people to other resources. But your link text should be descriptive so that people know where the link will take them.

Avoid words and phrases like ‘read more’ or ‘the website’. Instead, use link text that describes the page.

Links that have very little or no detail can leave people frustrated. It can make them doubt whether to click the link or not.

Good link text is important for people who use screen readers, too.

When documents contain many links, screen reader users may pull up a list of those links to find the one they want. Link text that has no detail about where the link goes can make this difficult. Or impossible.

Describing your links helps all your users.

How to write better link text for accessibility

Set tables up properly

Tables are a useful way of sharing complicated information. But they can cause accessibility barriers for people using assistive technology.

Sighted users can scan a table for information. They can see the visual difference between column and row headers quickly. And where the data in the table starts. Someone that cannot see the table cannot make these visual connections.

This is why it’s important to mark the rows containing these labels as ‘header rows’. This tells assistive technology users which part of the table they’re reading. Not all screen readers will pick them up, but they are useful to include.

How to markup table headers in Word

For simple tables:

- Select your header row

- Right click the row and select ‘Table Properties’. This brings up the Table Properties box.

- In the dialogue box, click the ‘Row’ tab, and select the checkbox that says “Repeat as header row at the top of each page”.

- Untick the box that says ‘Allow row to break across pages’.

- Select the ‘Alt-Text’ tab.

- Describe your table with alt-text that’s clear, descriptive, and concise.

- Click ‘OK’.

You can also pull up table options by clicking on your table and going to ‘Table Design’ in the ribbon across the top.

You should never use tables just to improve the appearance of your document.

You can check the table reading order by using the ‘Tab’ key on your keyboard. The focus should go from left to right in logical reading order.

For more complicated tables, you’ll need to add further markup. Especially for tables that contain split cells and merged cells.

Microsoft Support’s video on creating accessible tables.

Add alt-text to images

Alt-text is a written description of an image. Screen reader users need alt-text to understand the information an image contains. That includes charts, shapes, graphs and infographics.

Microsoft Office programs use artificial intelligence to generate alt-text. The problem is, generated descriptions are not always accurate. This is a common alt-text mistake to avoid.

You should always try to write your own.

We recommend switching automated descriptions off. That way, the accessibility checker can review your images and flag any missing alt-text as an error.

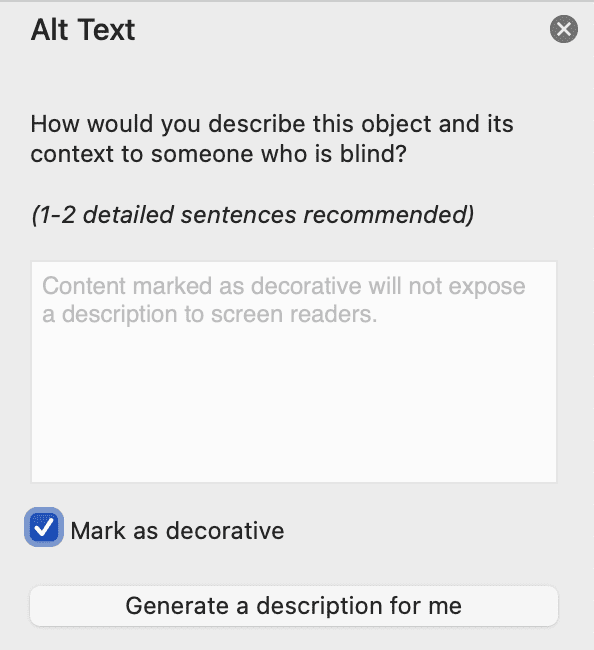

How to add alt-text to images in Microsoft Word

Add alt-text by right clicking on your image and selecting ‘Edit alt-text’. You can also add alt-text in the ‘Picture Format’ tab under ‘Alt-text’. Or, under ‘Review’ and ‘Check Accessibility’.

Always add alt-text to images. Unless they’re decorative, like clip art, in which case you can leave the alt-text blank. For decorative images, tick the ‘Mark as decorative’ box in the alt-text pane.

How to write better alt-text descriptions for accessibility

Use headings to structure your document

Using coded heading styles is essential for accessibility. But adding headings to your documents improves readability and navigation for everyone.

This is because headings organise your content. So it’s clear where the reader needs to go to find the information they want. But you need to make sure your headings follow a logical structure.

Your main heading, or document title should always be a Heading 1. Subheadings below that should be Heading level 2 (H2s). Subheadings beneath H2s should be H3s, and so on.

How to create a heading structure in Word

- Use the ‘Styles’ pane in Word to pull up a list of heading options.

- Highlight your text.

- Choose the correct heading level for the type of heading you’re adding, like a Heading 2 for subheading.

How to set a proper heading structure for accessibility

Use bullet points and numbered lists

Using lists is a simple and effective way of breaking up your content. Lists can help people using assistive technology understand the information on the page. They also help people who may struggle to read long walls of text.

For example, which of the following passages of text is easier to read?

There are many free healthcare apps available for your phone. To help you book appointments, order repeat prescriptions, check symptoms, view your medical records and manage certain conditions, like diabetes and asthma.

Or,

There are many free healthcare apps available for your phone to help you:

- book appointments

- order repeat prescriptions

- check symptoms

- view your medical records

- manage certain conditions, like diabetes and asthma

Always use Microsoft Word’s built-in formatting to create those lists. Choose from bulleted or numbered list options. We recommend using numbered lists when you want people to do things in stages or in a specific order.

Keep your bullet points short for readability.

Avoid using italics and overusing bold

Screen readers cannot always detect bold and italic formatting. You should avoid using them for emphasis.

Some screen reader user settings can announce this kind of formatting. But you should never assume this is possible or that every user has these settings on by default.

Italics can make words harder for people to read, too. Including people with:

- low vision

- dyslexia

- lower reading levels

Avoid unnecessary special characters

Screen readers and assistive technologies treat special characters differently from normal text. This includes punctuation, symbols and Unicode characters.

And even common punctuation marks like ampersands ‘&’, dashes ‘-’ and commas ‘,’.

Screen readers may skip them altogether or read something irrelevant to the user. This can vary depending on the type of screen reader a person is using.

In general, it’s best to avoid using any unnecessary special characters. Never rely on those characters to communicate meaning, without context.

How special characters can impact accessibility.

Do not rely on colour to show meaning

You should never use colour to express information. For example, just using green to show that an action is ‘done,’ or red to mean ‘outstanding’.

This can make your content inaccessible to certain people. Including:

- screen reader users

- people with low vision

- people with colour vision deficiencies (or ‘colour blindness’)

Using colour in this way means a large audience will miss out on the information you’re sharing.

Check colour contrast

It’s important to check whether your text and background colours are accessible. Most default colours in Word fail contrast checks when you use them with a white background.

Use colours for both the background and text that have good contrast. To be accessible, text that’s 14pt and below should have a contrast ratio of 4.5 to 1 (small or medium-sized text). For large text (above 14pt) the contrast ratio needs to be 3 to 1.

You can work these contrast ratios out with tools like WebAIM’s colour contrast checker. Or the colour contrast analyser.

Always avoid brightly coloured, or light grey text on a white background.

Write in plain English

Using complex language in your writing can be an accessibility barrier too.

Plain English gets your message across in a more effective way. It’s more concise and easier to understand. It puts the reader’s needs first. And it means you’ll reach a much wider audience.

The reader is also more likely to get what a sentence means the first time they read it.

Tools like Hemingway app can help. It highlights where your language is hard to read.

Note: the Microsoft accessibility checker won’t highlight complicated language as a barrier. But Word’s language tools will make suggestions on where your language could be more concise.

How to improve your writing with plain English

Check accessibility using the accessibility checker

Like most Microsoft Office programs, Word has a built-in accessibility checker. This is a useful tool that can help find any issues you may have missed. It also gives you tips on how to fix those issues.

How to use the accessibility checker in Word

- Go to the ‘Review’ tab

- Click ‘Check Accessibility’

- Go through the ‘Inspection Results’ in the right-hand pane

- Follow the ‘Steps To Fix’ below the inspection results window.

How to improve Microsoft Office content with the accessibility checker (Microsoft Support).

Making these fixes can make your Word documents more accessible. As well as more usable for everyone.

More resources on Word document accessibility

Make your Word documents accessible to people with disabilities (Microsoft Office Support)

Creating Accessible Documents (WebAIM)

Everything you need to know to write effective alt-text (Microsoft Support)

Related products